Liam Oakwood reports on the scale of logging in areas next to mountain ranges in southern lutruwita/ Tasmania. As he notes: ‘In the shadow of the mountain ranges of the deep South a steady defence of life on Earth is being mounted’.

Many moons ago I was a whitewater guide in training on the wild rivers of lutruwita. One of our riverine classrooms was the Picton; rising from the Southern ranges, perched above the vast ocean at the bottom of the world, it flows North between the craggy peaks of the Hartz range and the eponymous Mt Picton. Young Huon pines fringe dark tannin stained pools and tumbling rapids plunge through the deep forest. We would drink straight from the river, absolved of the need to carry water by the rushing stream that was both our carriage and our sustenance.

On a river trip to Judbury down the Picton and Huon, we emerged from lush forest and floated around a bend to see a blasted clearfell on a hillside, machines still picking over the tangle of forest debris like great metallic insects.

Our instructors were seasoned local paddlers and told us of how the river had changed as logging tore through the valley. The rainfall response curve of the river sharpened. It would rise and fall more quickly after rain, leading to higher and stronger flood surges as water rushed from the newly barren hills.

The tale of the Picton, of devastating logging operations nestled against the edge of world heritage wilderness, is one still in evidence across the island. The forests of the so called ‘Permanent Timber Production Zone’ are often scarcely distinguishable from those across the world heritage border. Giant trees soar above fern gilt glades, broken tops create hollows that teem with flocks of critically endangered Swift Parrots. A multitude of life forms coalesce from leaf-tip to root bottom, enmeshed in ways not fully known to Western science.

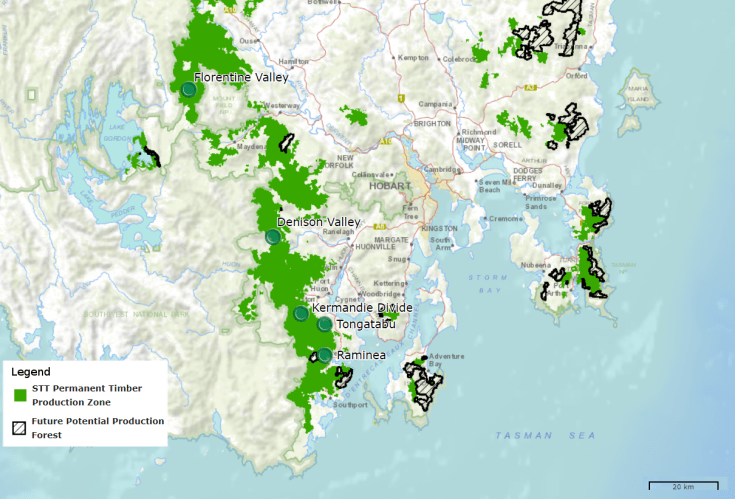

These strongholds of life on the fringes of lutruwita’s rugged mountains are under intensifying threat. LIDAR mapping techniques have been used to create a statewide canopy height map. Over the last year forestry coupes have been systematically appearing in some of the most significant remaining stands of mapped old growth. A giant log occupying a single truck trailer was spotted being hauled out one of these stands in the Florentine Valley, cradled between Mount Field and the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. A series of actions by community groups delayed the loggers blades amidst the grove of giant trees, but many of the giants were lost. A single one of them would be a noteworthy destination in mainland forests.

This pressure on high value areas is an inevitability of the business model of Forestry Tasmania. They have nearly exhausted the areas available to them, with efforts to replace native forest with eucalypt plantations failing to keep up. The impact of the 2019 fires and increased demand from Victorian timber mills has only exacerbated this trend, and the industry continues to push for access to the 356000 hectares of cynically renamed ‘Future Potential Production Forests’ that were briefly set aside as ‘Future Reserves’ following the 2012 forest peace deal.

Yet resistance is fertile. On multiple occasions when logging was discovered last year, forest activists of the Bob Brown Foundation and Grassroots Actions Network Tasmania rallied to launch stop work actions, carry out ecological surveys, seek legal intervention and shine a light on the destruction through old and new media.

A forest embassy in takayna, an ongoing blockade of Swift Parrot habitat in the South, and pending legal action testing the legality of logging in a coupe on the Kermandie divide ring in the new year with renewed resolve.

In the shadow of the mountain ranges of the deep South a steady defence of life on Earth is being mounted.

Leave a comment