A reflection from Anna Langford, currently in the Arctic Circle region of Norway.

People keep asking me why I have come to spend three months in the Arctic Circle. They need a beat of stunned silence to comprehend my answer, ‘to be cold’.

I’m well-practiced at riding out the response – the loss of words, usually followed by a guffaw of laughter and a light-hearted insult. And sometimes a nervous flicker in the eyes, as though I’ve just given myself away as a ghoulish creature who flinches at the touch of sunlight.

I have been travelling since January, when I chose to bail on an Australian summer in favour of an English winter. ‘What are you doing here?!’ people would splutter, upon finding out where I had come from. Had I accidentally stumbled into Melbourne airport and onto a flight to London while on my way to the beach?

My first northern hemisphere winter slunk away with unnatural rapidity in England and Spain. I planned out my European summer to avoid as much of the heat as possible (so, of course, to Ireland). And all through these midyear months, messages from home have had a common theme.

‘You lucky thing, being up there in the warmth.’

‘It’s cold and miserable here.’

‘I can’t wait for spring.’

Everyone’s favourite punching bag, a Melbourne winter.

Some friends would ask if I was homesick. Another bewildered silence would follow my response: ‘I am particularly homesick at the moment, because I’m sad to be missing winter.’

To curse winter and cold weather is such a natural part of day-to-day conversation that I didn’t notice its ubiquity for a while. Words like ‘foul’, ‘miserable’, and ‘bleak’ are our synonyms for cold, wet weather. Everyone knows what you mean when you say the weather is ‘bad’. If we were to say that a year had ‘a bad winter’, it would be assumed that we meant a winter that played its seasonal role too well, with a deeper, longer lasting icy ferocity than we were prepared for.

But I have come to crave and treasure cold weather with a vigour I might never have developed if winter’s existence wasn’t threatened. Our planet is growing dangerously hot. As climate systems spin out of control, a ‘bad winter’ now means a winter that is literally bad at being the way winter is supposed to be. And more and more of these new ‘bad winters’ stack up as each new year smashes temperature records.

There were mixed messages from family and friends about this year’s winter. Complaints about bouts of cold gave way to evidence that it was, indeed, a ‘bad’ winter there.

‘It’s so warm and sunny today, such a relief.’

‘The wattle is blooming early.’

‘It was 21 degrees today,’ reported my mum over the phone. ‘We went to the beach!’

‘Mum, I don’t want to hear that it’s 21 degrees in August. There’s no snow in places it should be blanketing the ground.’

‘Oh. Yes, true,’ she said, momentarily deflated. ‘But it was still a really nice day.’

How could I disagree? Warm and sunny with wattle blooming, taken completely out of context, sounds like a delightful day. What am I doing, guilt tripping people for enjoying pleasant weather? I half wished I had gritted my teeth and agreed instead of yet again being the climate crisis grinch who calls ‘the end is nigh’ during a light conversation.

But then I go online and read the news. 2024 is shaping up to be – surprise – the hottest year on record. The ski resorts are – once again – shutting up shop a month early. As I gaze out at the Arctic ocean, imagining its frozen core beyond the horizon, I try to forget the article I read this morning that told me the North Pole will be entirely ice-free every summer by 2050.

When I was nine years old, I remember being engrossed by one of my dad’s National Geographic magazines titled ‘The Big Melt’. I poured over the same few pages of that edition so many times. I didn’t understand a lot of the words, but the line that gripped me was ‘an Arctic without ice would be like a garden without soil.’ I remember when I still thought that we could never let something so startlingly wrong become reality.

After years of observing people continue to exchange out-of-date niceties about the weather in the face of neverending ‘unseasonable warmth’, I began to wonder. As it becomes more starkly apparent that we are losing winter as we know it, will we collectively begin to miss it? To yearn for it? Will something ancient and instinctive reactivate in more of us?

If we harbour an instinctive understanding of the necessity of winter, it doesn’t seem to serve a practical purpose for many of us today. In the industrialised world, humans have been disconnected from the seasons for generations. Our survival no longer depends on being tethered to their rhythms. Coles will stock tomatoes all year round.

But many peoples around the world who maintain deeper relationships with the land are feeling the loss of winter keenly. Inuk activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier wrote her book ‘The Right to be Cold’ about the existential threat that the loss of winter poses to Inuit people’s traditional way of life: ‘The weather, which we had learned and predicted for centuries, had become uggianaqtuq—a Nunavut term for behaving unexpectedly… Our sea ice, which had allowed for safe travel for our hunters and provided a strong habitat for our marine mammals, was, and still is, deteriorating.’

Watt-Cloutier knows that her plea to act on the climate crisis for the purpose of preserving winter will not be comprehended by many as a high-stakes fight.

She writes: ‘Indeed, the idea of “the right to be cold” is less relatable than “the right to water” for many people… the global connections we need to make in order to consider the world and its people as a whole are sometimes lacking. Because as hard as it is for many people to understand, for us Inuit, ice matters. Ice is life.’

Where I am now, in the Arctic Circle region of Norway, ‘ice is life’ might translate to ‘snow is life’. I am living with a family of Sámi indigenous reindeer herders, who follow wild reindeer across thousands of kilometers throughout the year, and depend on them for their meat and fur. You would think that a place where winter temperatures drop to -40C would be buffered from the impacts of climate change a little longer. But spikes of warmth are already starting to melt the winter snow too early, which can then re-freeze as a hard sheet of ice. The reindeer dig through the soft snow to find their winter source of food. But when it is suddenly sealed off by ice, they starve.

Closer to home are similar ancient relationships with winter. For thousands of years, First Nations people of the so-called Australian Alps have honoured the coldest months as essential for the integrity of the alpine ecosystems. In 2020, Ngarigo Professor Jakelin Troy translated a song of her ancestors from the Kunama Namadgi (Snowy Mountains) and found it to be a song sung in ‘a snow-increase ceremony’, performed to will the snow’s arrival in the autumnal months. As with the Arctic, snow is life to all who call the alps home. Common meanings of terms like ‘cold’ can be reversed: mountain pygmy possums rely on a thick blanket of snow to keep them warm through their winter hibernation. Without it, they die of exposure.

After leaving so many stupefied silences in my wake when I express my winter-philia, I realised that I didn’t have sufficient words to fully create a shared understanding of why I love the cold. I’m a skier, and all of us skiers share our eagerness for the first snowfall each year. But it’s not the ski-able snow by itself that is magic for me.

The ski resorts claim (in their dreams) that they will be able to continue making enough artificial snow to stay open for business, no matter how warm future winters get. Personally, I shudder at the thought of going to the alps to ski down thin strips of manmade snow, surrounded by bare ground and dead snow gums. I love shredding the pow, but I go to the alps to be enchanted by the whole world of its unique ecosystems that depend on cold winters. There is nowhere else like it in the world. If we lose winter, we lose the alps as we know and love them.

Though it isn’t our habit to wax lyrical about winter as we do about other seasons, I’m sure I am not alone in the dread I carry in my stomach at the signs of the cold months turning feeble and mild.

So, as I bat back messages calling me a crazy freak for my frost-seeking mission, and as I can feel beads of sweat rolling down the languishing form of the Arctic, I summon my fellow winter lovers out of the woods.

Right now we are lacking shared rituals and reasons to honour winter. How can we celebrate and appreciate it rather than simply craving its departure? All too soon, if we don’t act, we will get what we wished for – and I don’t think it will really be what we wished for.

Action is always the antidote to despair

Check this listing of groups active in the high country (available here).

Sign this letter to the Victorian premier, urging them to act to protect snow gum woodlands (available here).

Do this survey from Protect our Winters (available here).

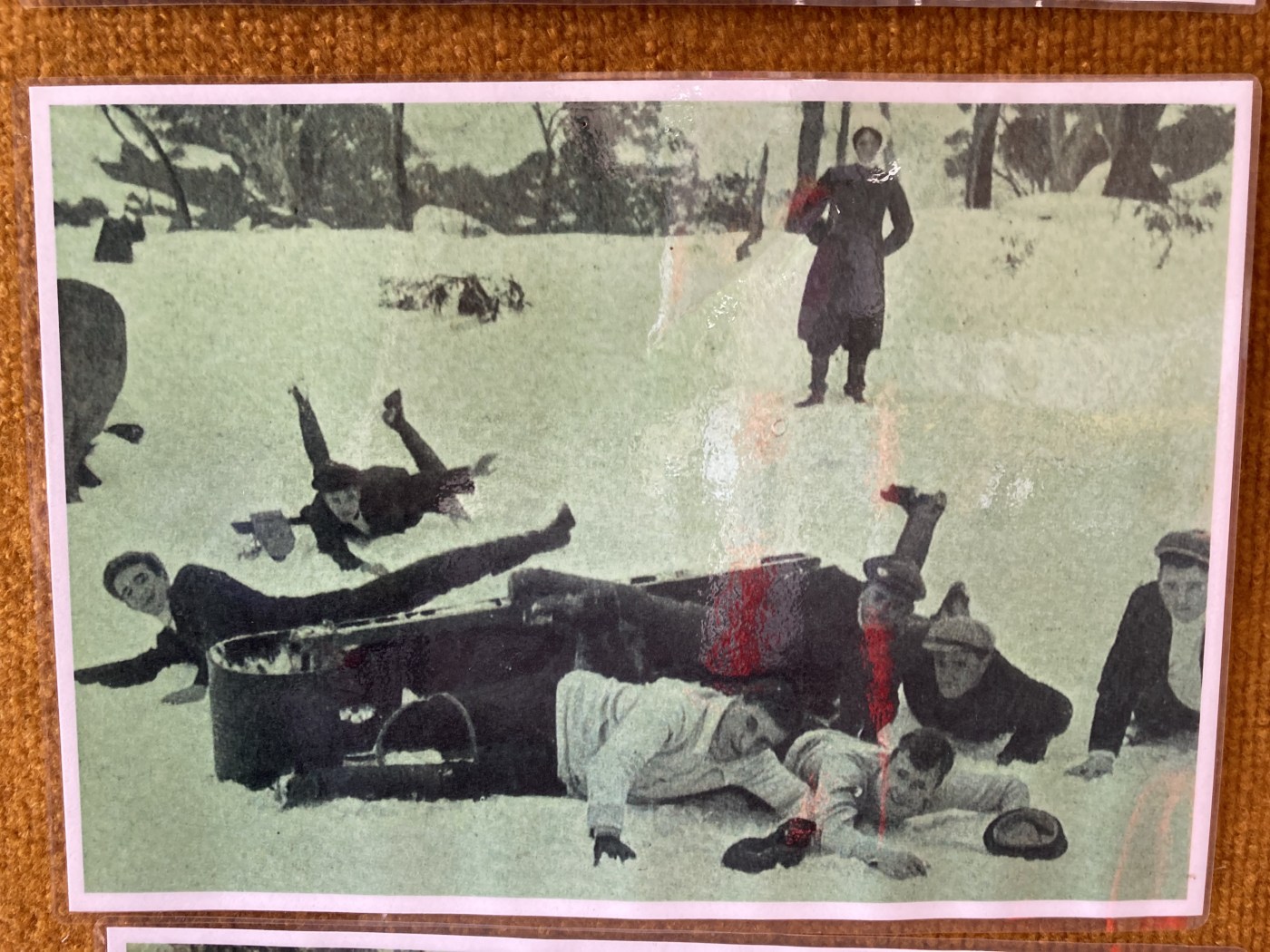

All images by Anna Langford. Header image: Better Days at Buffalo, taken when winters were cold enough to allow ice skating on Lake Catani.

Leave a comment