We know that climate change is reducing the overall amount of snow we receive in Australia. The snow pack has been in decline since at least 1957. We also know that the loss of snow is being felt especially at lower elevations.

We also know that as snow pack dwindles and the snow line climbs up the mountains that we have already lost a number of previous centres of snow culture – like at Mt Buffalo where there used to be a small resort with ski runs, and people would ice skate on Lake Catani, while the famous Buffalo chalet provided great holidays in the snow in a beautiful setting. The old ski lifts at Buffalo have now been dismantled.

In the 1920s and 1930s people could ice skate on the lakes in Mt Field national park in lutruwita/ Tasmania, including at the famous Twilight Tarn and there was even a small outdoors ice rink on the summit of kunanyi/ Mt Wellington, above Hobart.

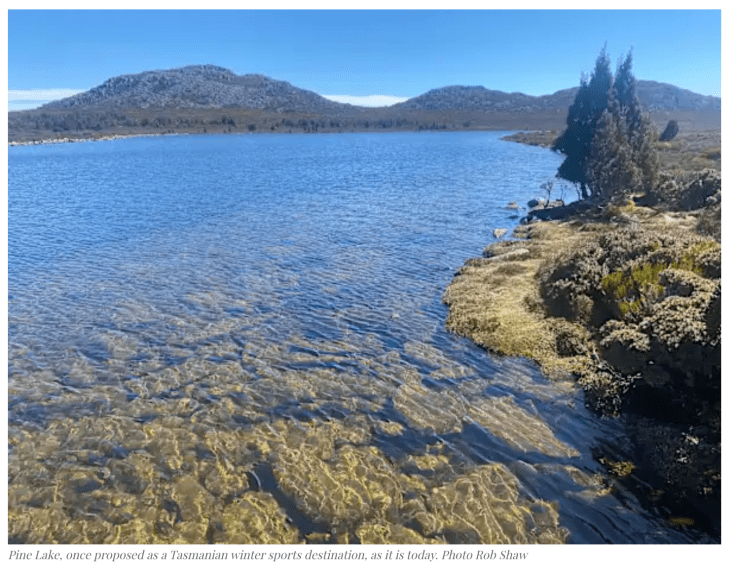

In the early 1900s, a popular ice-skating venue at the time, Pine Lake on the Central Plateau in Tasmania was chosen for the intention of establishing Tasmania as “the Switzerland of Australia” by establishing a “Ice yachting” venue (where specially built yachts could skim across the top of the frozen lake). Source.

The small resorts at Mt Mawson (Mt Field national park) and at Ben Lomond in the north east of the state really struggle to get enough snow cover to justify opening the ski tows.

Spring skiing in the mountains of lutruwita/ Tasmania was a thing up until the 1990s. Now good snow pack in the spring months is a rarity that must be grabbed if you have the chance.

Kiandra in the Snowy Mountains was the birthplace of skiing in Australia (as pointed out in this recent podcast from Protect Our Winters). Australia’s first T-bar lift had been installed on Township Hill near Kiandra in 1957. Now the valleys and hills around the old settlement rarely hold skiable snow for long.

Selwyn Snow Resort, Australia’s most northern resort, was badly damaged during the 2019-2020 bushfires, however has now been rebuilt. While it still has ski lifts, its more modest elevation (compared to the nearby resorts in and around the Snowy Mountains Main Range) does mean it struggles to have continuous winter snow.

I learnt to ski at Lake Mountain in Victoria – now mostly gone in terms of regular snow pack, and at Mt Stirling – often now a considerable walk up from Telephone Box Junction. Growing up on the eastern fringe of Melbourne, our family would head up to Donna Buang when the snow was on, and later as a teenager I would walk or ski down the road to the rocky summit at Ben Cairn. Now rarely skiable.

Then we have the Tallangatta Ski Club (TSC), which was formed in December 1947. They have a small lodge and rope tow on the north facing slopes of Mt Wills, close to Mt Bogong.

And the lodge at Mt Franklin in the ACT was built in the summer of 1937-38 for the Canberra Alpine Club and acted as a base for winter adventures for many years.

In the 1980s and 1990s, limited downhill skiing took place at Corin Forest near Canberra. Now it usually receives natural snow about 6 times per winter. For most of the winter they have to rely on snow guns to provide snow cover.

Anyone who is not blinded by their climate denier identity politics can see what’s going on.

You have to wonder how many resorts and snow focused communities we will lose before we see meaningful action by the snow sports community – this should be lead by the ski companies, resort management and larger businesses like those involved in construction and property.

Resources

You can read more about climate impacts on low elevation resorts and mountain areas here.

You can find the Protect our Winters report Our changing snow scapes here.

Action is always the antidote to despair

Check here for some links on getting active, tackling climate change, and supporting local environmental and climate action groups.

How can the snow industry respond?

With a few notable exceptions, ski resorts have been operating under a business as usual approach for a long time. Now is the time to get active.

Resorts have political muscle, but don’t use it. Resorts are collectively bringing about $2.4 billion a year into the economy. They employ many thousands of people directly and through the valley tourist towns that exist along the main routes from capital cities to the resorts. It is one of the biggest employers in regional Australia, accounting for the equivalent of more than 20,000 full-time jobs. Summer visitation in Victoria alone adds a further $146 million to that state.

Given their economic weight the resorts are embarrassingly absent from national debates about climate.

The resorts need to get their act together and become a political force. That means using their influence to call for deeper emission reduction cuts and energy transformation.

The resorts need to get their house in order. For starters, they must shift all their operations to rely on renewable energy. That’s the first and most significant thing they need to do. There are some steps forward and many examples of resorts overseas doing fantastic work on this front. How is it that in 2024 we are still heating our lodges with gas and running our lifts on diesel?

Skiers and riders need to get their act together. Yes, I know people go to the snow for a holiday and want a break from negative news. They want to switch off and enjoy the snow. But there are many things we can do, and humans tend to trust friends and family over scientists for forming views. Resorts should be helping people to understand that without meaningful action to reduce emissions now, we will see the end of winter as we know it within our lifetimes. It needn’t be grim or shouty, but there is a role for resorts in educating their visitors. They could even reward people for making good decisions, for instance by seriously getting behind mass transport to the mountains.

Hardcore skiers and riders also need to step up. With a dynamic group leading efforts at Protect Our Winters and many new projects underway, now is the time to sign up, get involved, and bring your skills and passion to the movement.

What we do matters. Yes, I have been overseas to ski, four times now. Each trip was mind bogglingly good. But it came at a cost for the planet. The Australian aviation industry’s CO2 equivalent emissions jumped from more than 10 megatonnes in 2002-03 to more than 23 megatonnes in 2018-19, a pre-pandemic peak. And I have contributed to that.

After lockdowns, and a several very sad local winters, many of us are keen to head north and get into some pow. But what are our responsibilities? In a world where people will continue to fly for recreation, and where the climate cost of those flights remains high, some logical options are:

- Go for fewer longer trips when you do go overseas, rather than multiple short trips

- Don’t take short haul flights to get to the skifields

- Stay well away from those ridiculous helicopter flights they have at some resorts. Of course, any resort that was serious about climate change would cancel these operations as a first step in becoming responsible corporate citizens.

Leave a comment