The Tasmanian National Parks Association (TNPA) recently dedicated an issue of their newsletter to the question of how to manage wild fire in Western Tasmania. As has been widely noted, including here at Mountain Journal, fires having been getting more intense in western lutruwita/ Tasmania since a ‘tipping point’ sometime around the year 2000. Since then, there has been an increase in the number of lightning-caused fires and an increase in the average size of the fires, “resulting in a marked increase in the area burnt”.

As TNPA notes in the introduction:

The direct impacts of climate change for Tasmania are changes to weather patterns with corresponding changes to levels of temperature, rainfall and evaporation – most likely a warmer, drier climate overall.

The outcomes of some of these changes are beyond our ability to influence. For example, there are no options for protecting an entire landscape from drought, although it may be possible to save examples of individual species.

As discussed in the following essays, the increased frequency and intensity of wildfires is already resulting in demonstrable impacts on some of Tasmania’s most highly valued species and ecosystems (paleoendemics and alpine ecosystems) and options do exist for how it is managed.

This edition tries to grapple with the changing nature of how we need to interact with wild places. Andry Sculthorpe, who manages the Country and Culture division of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, says that prior to invasion, these ‘landscapes were not wild places; they were creations of our people. People travelled from place to place, burning Country and ensuring that hunting grounds were maintained and foods could be gathered’. As invader culture grapples with that reality, we must also accept that in a time of rapid global heating, we must increase our intervention in terms of managing landscapes and fire if we are to have a hope of retaining the forests that we know and love.

The TNPA say:

The potential for climate change to significantly alter ecosystems on a planetary scale in the near future means that it is not just another conservation issue but one which requires a reappraisal of our approach to nature conservation. The rationale behind the traditional scientific approach of ‘reserving’ an area of land was to provide protection from extinction for its species and ecosystems from most human impacts and to maintain biological diversity and other natural values and processes. However, the impacts of rapid climate change challenge this approach.

David Bowman, from the Fire Centre, school of Natural Sciences, University of Tasmania, writes that human-induced climate change makes Tasmanian protected areas fire management more difficult.

He says that

- Rapid attack of new start fires in remote areas is essential, and where this fails,

- Fire managers need to decide what sections of the fire to try and contain

- He also sees prescribed burning as a tool to create breaks between fire tolerant and fire sensitive vegetation communities.

He does also note that prescribed burning is becoming more difficult because of anthropogenic climate change, with shrinking safe ‘windows’ for when fires are able to be lit and controlled.

He notes that:

Fire managers have a range of approaches to managing lightning fires, which typically occur in remote areas. These include surveillance and detection, and rapid attack to extinguish the starts before they become uncontrollable, using specially trained remote-area fire crews combined with aerial firefighting. Extremely large lightning storms, however, overwhelm these approaches because there are too many starts to attend to at once, as well as necessary delays in identifying ignitions because of poor visibility and the sometimes-delayed emergence of the fire. Because of dry conditions that favour lightning ignitions, inevitably some fires grow to such a size that rapid extinguishment is impractical. Because firefighting capacity cannot cope with the surge demand of massive lightning storms, fire managers must implement a process of triage.

Triage is a difficult process of selecting which fires to prioritise fighting, and in what sections of the prioritised fires to concentrate their efforts.

He also says that:

There are necessary difficult trade-offs in fire-risk mitigation. These include: settling on what areas will be identified as the highest priority for protection, what areas will be treated with prescribed fire and how they will be burned, what sort of firefighting approaches (such as the use of firefighting chemicals and cutting of fire trails for vehicle access) are ecologically sustainable, how much funding should be spent on fuel reduction and firefighting.

Dr Steve Leonard, senior fire ecologist, fire science co-ordinator, DNRE, elaborates on the reality of two types of vegetation, with different needs when it comes to fire, co-existing very close to each other:

A characteristic of the TWWHA is the juxtaposition of ‘fire-dependent’ ecosystems such as buttongrass moorland and eucalypt forest, that require periodic fire to maintain their structure and function, with ‘fire-sensitive’ systems that may be rendered locally extinct by a single fire.

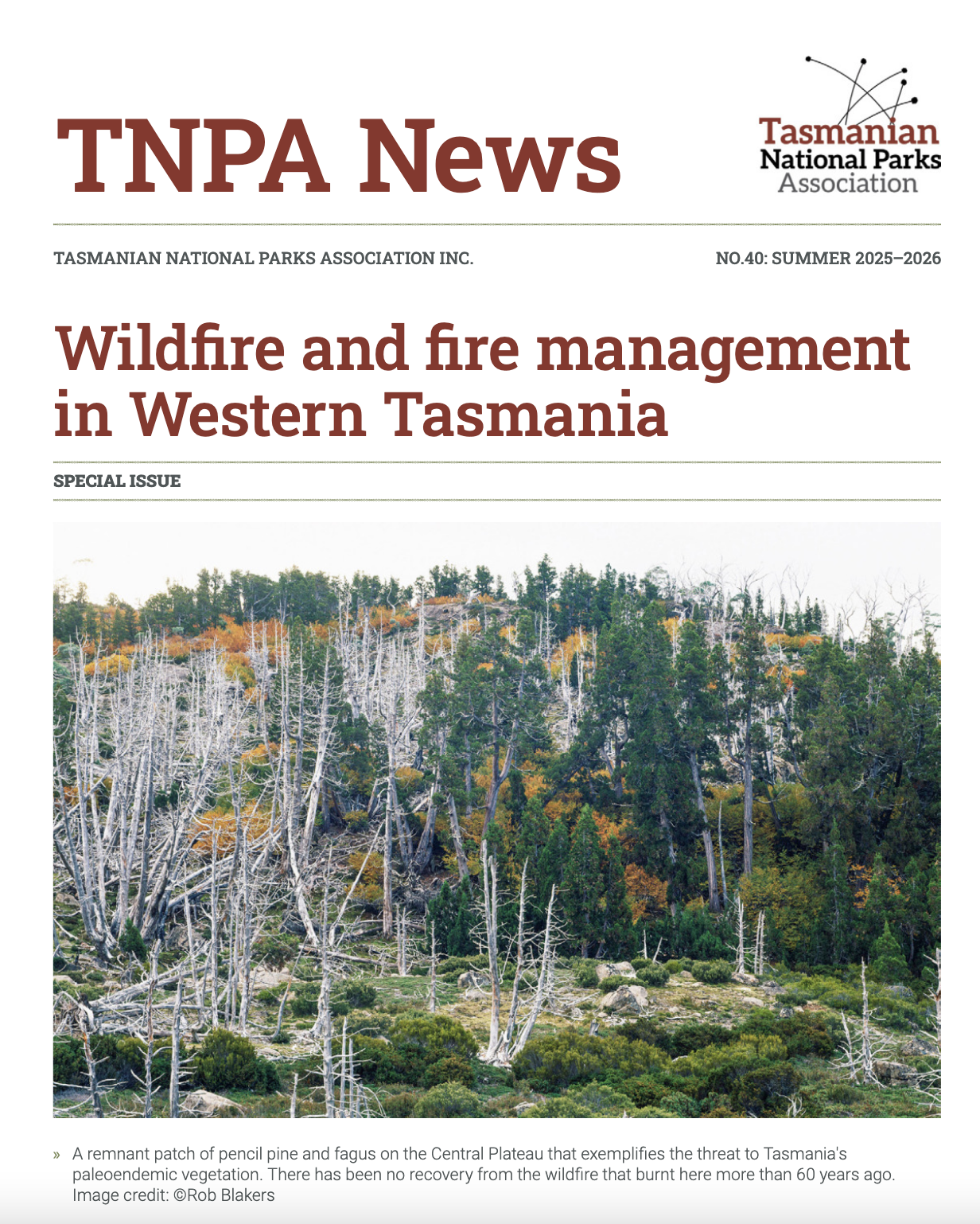

The latter group includes paleoendemic rainforest and alpine vegetation dominated by iconic species such as pencil pine (Athrotaxis cupressoides), King Billy pine (Athrotaxis selaginoides), Huon pine (Lagarostrobos franklinii) and fagus (Nothofagus gunnii). These species represent ancient lineages that evolved in environments where fire was rare.

With careful planning, prescribed burning in treatable areas can create landscape-scale firebreaks between untreatable areas (ie areas of rainforest, etc)

Other sections of the newsletter cover

- the threat to paleoendemics, by Rob Blakers

- Havoc for King Billy Pine, by Andrew Darby

- Andry Sculthorpe, who manages the Country and Culture division of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, discusses the need to reintroduce culture fire into the landscape

Katy Edwards, state fire manager, PWS, DNRE notes that Tasmania’s fire managers are navigating a landscape transformed by climate change. Their work now requires not just firefighting, but ecological stewardship, cultural sensitivity and scientific innovation. The stakes are high: protecting one of the world’s last temperate wilderness areas, the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA) from the growing threat of fire.

Parks Service have responded by doing various things:

- Investing in the latest early warning systems: There are two major streams of work, satellite detection and ground-based camera detection

- Rapid Response: Building on the early detection of new fire starts, PWS focusses on rapid initial attack to keep fires small if possible

- Fire prioritisation: When multiple ignitions occur on PWS land (e.g. following a lightning event) it is necessary to rapidly identify which ignitions pose the greatest risk to natural and cultural values and thereby prioritise a response

- A Fire Management Plan (FMP) for the TWWHA was finalised in 2022

- training of PWS staff in firefighting roles

- a Fuel Reduction Program

Leave a comment