The 2024/ 25 fire season was a long one in south eastern Australia.

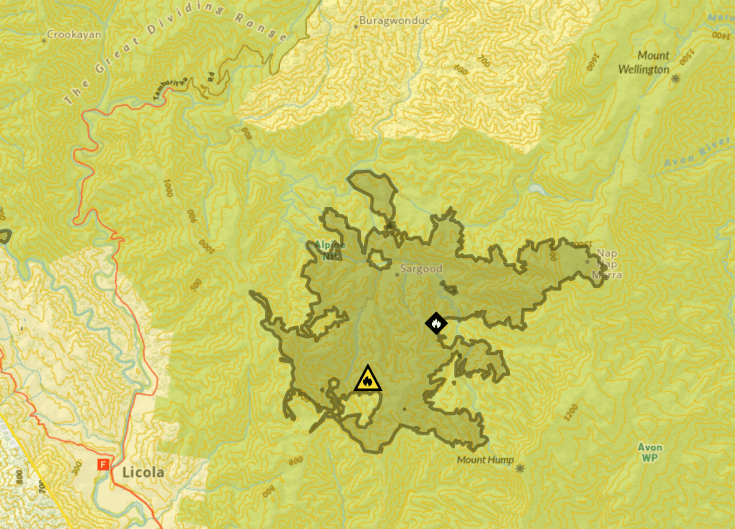

While there were large and destructive fires in western Victoria (particularly in the Grampians (Gariwerd) National Park and Little Desert National Park – details here), there were no enormous ones in the mountains. But if you track what happens in the high country, you will recall that we did have a number of significant ones last summer, including the Mt Matlock fire in the Thompson River catchment (which provides drinking water for Melbourne) and the Mt Margaret/ Licola fire, which grew to around 5,600 hectares. There are some resources on these fires available here.

There is a significant story from this latter fire which is worth retelling.

Getting the priorities right

In the case of wild fire, the authorities will always prioritise human safety and human assets over protecting ‘natural’ assets (ie wild places like national parks). This is understandable. However it highlights the fact that we sometimes simply don’t have the resources available to do both: that is protect humans and their things, and also protect important ecological assets like old growth forests, rainforest, peatland and so on.

With the Mt Margaret fire, incident controllers did a brilliant job of balancing the need to protect both types of assets.

Incident controllers developed a set of priority objectives for the fire control strategy. The strategy then informs how resources (trucks, aircraft, bulldozers, ground crews) are allocated. In the case of this fire, three priorities were identified:

- to protect the Licola community

- to protect cultural values along the Wellington River, and

- to stop the northern spread of the fire into the Wellington high plains area. This area is a ‘fire exclusion’ zone on fire maps and fire managers applied air and ground resources in an effort to keep the fire out of the fire damaged snow gum woodlands on the Wellington Plains.

Many people will be aware that this area includes the Avon Wilderness Park, the much loved Lake Tali Karng, and special high plains country that stretches from Gable End up to Macfarlane Saddle. It is hugely popular with bush walkers.

At the time, Friends of the Earth and the Victorian National Parks Association wrote to the head of Forest Fire Management Victoria (FFMV), noting that the fire threatened important natural assets, including:

- the area around Lake Tali Karng, which is highly significant to GunaiKurnai traditional owners and contains old growth mid elevation forests. It is also a hugely important recreational location, which attracts thousands of bush walkers each year, which in turn helps support economic activity in Licola

- remnant old growth Alpine Ash above Tali Karng along Gillios Track. This area has been burnt previously with considerable loss of old trees. The remaining forest has great ecological significance (see image below) given the ongoing loss of Alpine Ash forests across north eastern Victoria, and

- the Wellington Plains. The snow gum woodlands on the Wellington Plains have been impacted by multiple fires starting with the 1998 Caledonia River fires. Local surveying shows that another fire will impact on the young – and highly flammable – regrowth and potentially cause local ecological collapse of these systems at a large scale.

FoE and VNPA urged that resources be allocated to protect these areas.

The incident controllers deserve credit for prioritising ecologically sensitive areas in managing this fire. And the ground and air crews did a fantastic job of working to meet the objectives of the fire control strategy.

In the context of looking after ecological assets in the higher country, the work included ‘dead edging’ to stop movement of the fire: this is a term used to describe perimeter burning of an area in mild conditions prior to the arrival of the fire front. This involved crews moving into quite remote areas on the Wellington high plains. Air craft were also dropping retardant and water on the dry ridgelines around the fire where safe to do so (and well away from water lines and streams). Many of the south facing ridges, which are often wetter and less likely to burn, were very dry this summer.

They worked successfully to keep the fire from burning up Riggall Spur, which could have brought the fire onto the Wellington Plains in the Spion Kopje area.

They also worked to keep the fire out of the Carey catchment, where fire impacted alpine ash forests have been reseeded through the state government Ash Recovery program.

The fire was ultimately contained by rainfall in mid March.

As a firefighter, I have often seen crews pulled out of forested areas in order to protect human assets. This often leads to heart breaking outcomes. Best practise fire fighting occurs where incident controllers plan to protect both. The Mt Margaret fire is a great example of firefighting that ensures that fire sensitive vegetation and landscapes are protected.

HEADER IMAGE of the Mt Margaret fire is from FFMV.

Leave a comment