All of us are drawn to nature. For some people, that might be a pleasant view of a park from a window. For others it might be an epic paddling trip down a river through a wilderness area. It’s a deep need we all feel in some way. But as there are ever more people on the planet, and more people wanting to go walking and exploring wild areas, the impact of exploring adds up.

Informal trail networks can become degraded from over use, and the untracked zones shrink a bit every year as more people visit the wild places. It’s a dilemma for land managers and also for all of us who love to explore these places.

In this article, Josh Hamill explores the question of how recreational hiking can coexist with the preservation of wilderness areas (he describes wilderness as ‘nature as it is’).

Josh explains that ‘his piece is best understood within the context of my conversation through the video “My Issue With Modern Hiking Trails”. What follows aims to elaborate on and/or clarify a number of ideas presented throughout that video’ (available here).

Wilderness is purity.

It is life without intrusion, without the overbearing influence of mankind. Our way of life no longer fits into the sustainable cycle of the natural world – we take from the Earth, but we care not for giving back. Nature is merely a resource to be exploited, even in the context of our beloved outdoor activities. There is a separation between us and our modern world, and the natural world. It is why nature calls to us in ways that we are perhaps unconscious to.

To marvel at a tall forest of mountain ash, or to feel the fresh air from the sea and hear the sound of the waves, to stand atop a mountain and be surrounded by an amphitheatre of peaks and shades of green – the horizon stretching on into an endless haze.

We mightn’t be able to articulate the feelings these images conjure, but we are drawn to these experiences, nonetheless. We feel a distinct connection to the natural world – we known when we are experiencing that connection, even to the smallest degree. The importance of wilderness is universally and unconsciously understood, even though we take it for granted.

A walk in the city park, the sights of greenery within a bland sea of grey – does this not briefly ease your mind? It is of no surprise that we actively seek out nature to reconnect – not just with ourselves, but with the greater world around us. And to an extent, this connection is measurable. Does the city park not differ from Tasmania’s world heritage listed wilderness areas, or from the vast expanses of the Victorian High Country (the latter of which only offers pockets of true wilderness)? You can step further and further into the natural world through the reduction of mankind’s influence, but this is becoming increasingly difficult to achieve, and viewed more so through the lens of exploitation.

To find a complex of huts in the middle of the wilderness, or to follow a boardwalk that cuts through the heart of a landscape – you understand that this infrastructure is an intrusion to the purity of that environment. Perhaps not to the extent I see it, but you cannot deny that such additions are imperfections.

They don’t fit in.

I can’t blame you if you don’t understand. Wilderness is a misunderstood concept in the modern world – wilderness is nature in its purest form. It isn’t a landscape scarred by a network of roads and trails, dotted with huts and modern luxuries. It is a world far removed from our concepts of what nature should be – wilderness is nature as it is.

Why do I make this distinction? Because it directly relates to an activity that binds us together – walking. Specifically, the experience of walking in nature and defining the soul of the activity. Or, at least, expanding upon the reasons why I think modern hiking developments do a disservice to the act of recreating in nature.

How does recreational hiking coexist with the preservation of wilderness?

Walking is the purest form of transport through the natural world. To walk through a natural landscape is to become a small part of it – to connect with the greater world around and underfoot, to travel as our ancestors have for many thousands of years. Walking is our heritage – unnecessary in the modern world, imperative in the wild.

With recreational walking, however, it is our duty to ensure that we leave no lasting impression – that we refrain from interrupting the cycle to the greatest extent that is required. Where we influence that cycle, we by consequence ruin the purity of the environment.

Is it fair to suggest that walking through an un-tracked environment is an unnatural interruption? No, it is as all animals do. Then, of course, we have repeated use: the formation of a track. In a sense, this too is a natural occurrence – it is, again, what animals do: find the path of least resistance. This is the natural curation of a trail, but it does come with its flaws when inserted into the context of recreational hiking: namely erosion and environmental degradation – flaws that modern trails seek to eliminate, but they do so at a cost.

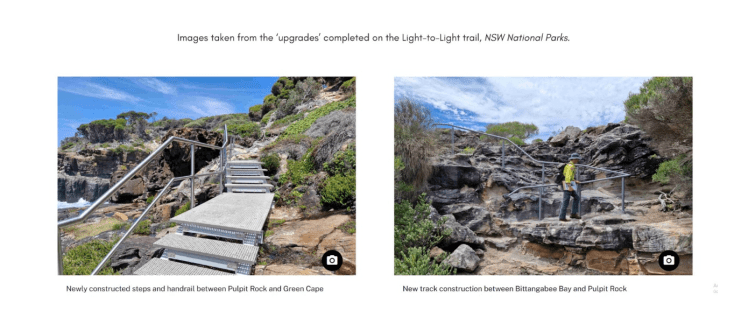

Modern trails exchange ‘natural purity’ with an engineered solution. In the same manner that excessive human foot traffic creates unnatural erosion, engineered countermeasures are an unnatural intervention. These interventions, while they don’t necessarily have to be, are damning to soul of wilderness exploration. They seek to define an environment, rather than integrate within it; and in doing so, the essence of wilderness is lost. Adventure and exploration become curtailed, replaced instead with a curated experience.

How can you have a hut in the wilderness? The mere existence of said hut means that it is no longer wild. Transpose this thought onto the way in which modern hiking trails are constructed – is the infrastructure not intrusive and out of place within the context of the greater environment? A better question may be: can infrastructure exist in a way that promotes recreational hiking without excessively sacrificing the purity of the natural world?

I believe it can. There will always be a sacrifice to the purity of the environment if we do anything beyond basic, animalistic travel, but to say that all modern infrastructure is a stain on the natural world is an extreme perspective. It depends on the context and how the infrastructure adds to the natural experience, rather than detracts from it. The sight of metal, for example, is one that consistently detracts from the natural experience (in my opinion). It also depends on what purpose the trail serves.

What is the purpose of modern hiking trails?

Increasingly, we are creating trails for sightseeing rather than ones that seek to foster a true connection with the natural world. We commodify nature as an idea to sell rather than an experience to share – not with each other, but with the world around us – and the implementation of infrastructure within this context only further promotes the purpose that the trail serves. Look at the infrastructure found on a “great walk” in Australia or New Zealand versus what is found on a normal, though maintained hiking trail. What does the infrastructure promote? Luxury or conservation? Are we coexisting with nature or exploiting it? There is a stark difference between a duckboard installed above a fragile alpine bog and a series of huts equipped with amenities expected from a 5-star hotel.

In evaluating our influence on the natural world, think of what problem the infrastructure aims to solve. Does it seek to preserve the environment or abuse it for our personal gain? To make the inaccessible accessible – a particularly one dimensional and selfish ideal: it sees the natural world only from the lens of recreational access, rather than the greater cost of allowing for it on a broader scale. It forgoes the reality that nature is accessible – but not in all of its shapes and sizes. There is beauty and connection to be found in all aspects of nature. There is terrain that is widely accessible and terrain that is not – to seek to change this is to interfere with the purity of the natural world.

The fact that there are some who cannot access the highest echelon of technical terrain (for whatever reason) doesn’t suggest that it must be made accessible to satisfy the needs of one versus the needs of the environment. Recreational access and personal satisfaction is not the whole purpose of nature – the world doesn’t have to serve our every need. Modern hiking trails seemingly seek to bend nature to our will, rather than promote our integration into the environment.

The consequence of the pursuit of the accessibility ideal is the dwindling of our wilderness, because the wilderness no longer exists – it is no longer pure. There are very few places in Australia, let alone on Earth, that are truly wild. Many places merely offer a glimpse into the natural world, a world you can return from through a short stroll to the car park. What if said car park wasn’t there? Or the handrails festooning the cliff line, the steps carved into the rock, the trail cut through the forest, the road to the carpark itself? Have you thought about what is lost when infrastructure is introduced?

Wilderness – purity- isn’t something to be exploited. It isn’t for our pleasure. It isn’t wholly for our gain. It is the remnants of a world we have lost. When constructing our gateways into the wild, we should be seeking to mimic what is desirable in the natural world, not what is desirable in our cities. When did we suddenly seek to prioritize functional accessibility over conservation? Without conservation, there is nothing to distinguish a walk through a city park from a walk through a national park – and that is an important distinction.

We seek out the wilderness (or our idea of it) to escape into a world that is pure and free from our influence. The soul of walking is allowing yourself to become a part of the natural world. Modern intrusions don’t allow for this – the connection will forever be shallow, devoid of what it really means to be in nature.

Josh Hamill – Better Hiking.

Josh is a hiker and amateur mountaineer based in the Victorian High Country – passionate about outdoor exploration and wild places.

Josh is a hiker and amateur mountaineer based in the Victorian High Country – passionate about outdoor exploration and wild places.

You can find more of his work via the following links:

https://www.instagram.com/betterhiking/

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvNqKFqP06AQZRSQ_CCjxRg

Leave a comment