Horses are beautiful animals. But wild populations do not belong on public land in the mountains. One of the longest running campaigns in the high country has revolved around the efforts to have sheep, cattle, and then horses, removed from the mountains. This is one of the good news stories of the high country: governments are acting to reduce numbers of animals roaming our national parks.

In this excerpt from the 2026 Mountain Journal magazine, Linda Groom explains some of the story behind this long campaign in NSW.

Feral horses in Kosciuszko – a political change in direction

[Header image: Mike Bremers]

Our mountains exist in a changing political landscape. There are recent signs from NSW that some of those changes are for the better. In December 2025, the NSW Parliament passed a bill to repeal the Kosciuszko Wild Horse Heritage Act (NSW, 2018). The repeal bill received support from both sides of NSW politics. It means that Kosciuszko’s feral horses, also known as brumbies, can now be managed like any other damaging feral animal, without any special protection.

That excellent decision was part of a pattern of improved protection for Kosciuszko’s native plants and animals from feral horse impacts. In 2024 the NSW government responded to spiraling feral horse numbers in Kosciuszko by recommencing aerial shooting. The government also published a new management plan for feral horses in Barrington Tops National Park. That plan has a target population of as close to zero horses as is practicable.

How was that victory achieved?

What follows is my personal view of the steps to victory, based on my experience as a Volunteer Co-ordinator with the lead organisation of the campaign, the Invasive Species Council (ISC).

[Above: feral horses, with damage in the foreground]

Start with science

When an environmental campaign is place-based, it is a great advantage to have an extensive body of scientific studies relating to that particular place. In 2018, the NSW Threatened Species Scientific Committee determined that feral horses were a key process threatening Australia’s native plants and animals, consolidating decades of scientific evidence.

Provide a platform for Indigenous voices

In 2018, Aboriginal elders from East and West of the Great Divide organised the Narjong Water Healing Ceremony at the birthplace of the Murrumbidgee River in northern Kosciuszko. They described it as a ‘place that should be protected within Kosciuszko National Park, but is being desecrated by hard-hooved feral animals and empty promises of protection and preservation’.

Wiradjuri man Richard Swain attended the Narjong ceremony. He works as Indigenous Ambassador for the ISC and has been a powerful voice for protecting the high country from all feral animals.

Talk to strangers

In any environmental campaign, an early step is to talk to friends. We certainly did that. We gave presentations and sent newsy updates to bushwalking clubs and environmental groups. The Conservation Council of NSW and the National Parks Associations of the ACT and NSW were particularly helpful in spreading the word.

Talking to friends is an important first step. Some of the friends we spoke to turned into volunteers, and many became donors to the campaign.

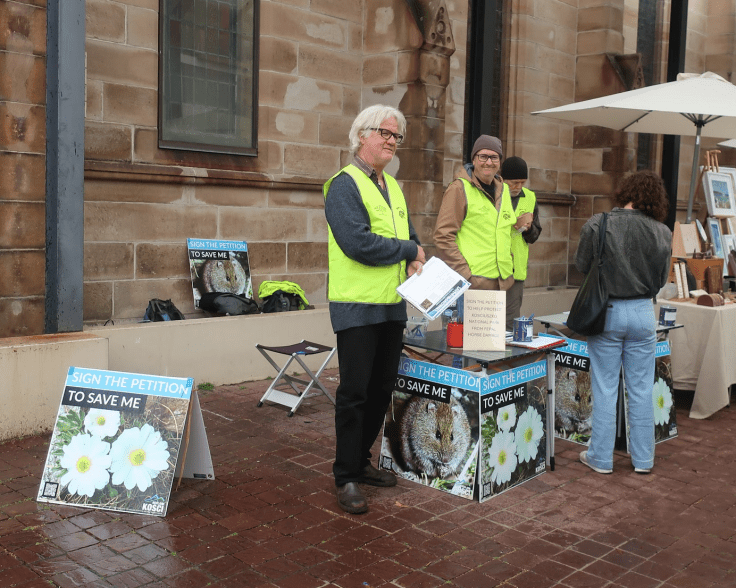

Talking to strangers is even more important. As in many campaigns, we spoke to strangers via the media. In this campaign, however, we used an additional channel. We ran tables at markets, on footpaths in spots approved by local councils, in national parks, and in paid-for spots in shopping centres. At the tables, volunteers asked passers-by – complete strangers – to sign petitions and submissions. Each signature involved a one-to-one conversation. Over three petitions and one round of encouraging submissions to a government inquiry, our volunteers engaged in at least 26,000 conversations with strangers between 2018 and 2025.

[Image: petition table in Sydney]

It takes a bit of nerve to set up a petition table in a town that is a day or two’s drive from wherever you live. We started with locations that were near to where volunteers lived, then encouraged the volunteers to try petition-tabling in more distant places. The volunteers had to cover all their own costs, but had the satisfaction of seeing the signatures steadily increase.

Talk to politicians

To convince the politicians, we used a combination of the scientific evidence, and evidence of the social license for change from the petitions and letters from constituents.

The salaried staff at the ISC undertook most of the work of lobbying politicians. It needs evidence conveyed with courtesy and patience. It needs clarity about what you want, rather than vague requests to ‘do more’. And it needs the ability to be able to switch modes and talk to the donors who will fund your ability to continue to talk to politicians. The ISC staff have those abilities in spades and I stand in total awe of their skills.

And some luck

The campaign to protect Kosciuszko from feral horse damage also benefitted from luck. Luck in the form of divisions and distractions among the groups that opposed us. The re-homers – those who generously accept feral horses from national parks and care for them on their properties – disagreed with those who thought re-homing was a cop-out and who vandalised the trap yards used by the NSW Parks Service to gather feral horses for re-homing. There was an even broader division between brumby supporters who discussed strategies around campfires while the sausages were sizzling, and supporters who discussed animal sentience and regarded sausages as an abomination.

One group of feral horse supporters raised funds to pay Airborne Logic, a professional air survey company, to take air images of parts of northern Kosciuszko with the aim of showing that there were far fewer horses than the official counts. Airborne Logic produced images of stunning clarity and used a combination of AI and human checking to count the horses. The results confirmed, rather than contradicted, the official estimates. The media pounced on the air images which showed, in new and impressive detail, the extent of the feral horse tracks criss-crossing northern Kosciuszko.

Many environmental campaigns face opposition from well-funded developers or large companies. We were lucky enough to avoid that.

[Above: gathering petition signatures at Charlottes Pass]

[Above: gathering petition signatures at Charlottes Pass]

What next?

There is still some work to be done in translating the NSW Parliament’s decision to repeal the Kosciuszko Wild Horse Heritage Act into formal plans and operations. Under the repeal bill’s transition provisions, the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service has until late 2027 to produce a new plan. Until then, the old plan, with its aim of retaining 3000 horses in the Park, remains in place. Three thousand horses are still causing damage and threatening native species. We’ll be working towards a target of ‘as close to zero as practicable’.

Linda Groom is a volunteer co-ordinator with the Invasive Species Council.

February 19, 2026 at 9:11 pm

Evidently you have never done a horse or elk slalom at Jackson Hole, Wyoming ❗️