In the 2023 print edition of Mountain Journal (available as a pdf here), we acknowledged the legacy of Maisie Fawcett. Maisie was an ecological pioneer who is remembered for her ground breaking work in the Victorian high country. In this story from Karina Miotto, Latrobe University, Maisie’s legacy is considered in the broader context of her work as a woman operating in a time where society – and science – were heavily dominated by men.

A quiet achievement took place last summer in the Victorian Alps. Scientists gathered to re-measure botanical plots first set up more than 75 years ago by one of the pioneering women in science. This is the story of that woman.

In the modern world, women are now finding their voices in the fight for their rights, equality, and respect in both personal and professional spheres. This progress, although significant, is just the beginning of a long journey towards complete recognition and liberation from the scars inflicted by centuries of patriarchy. But, let us take a step back in time and imagine the challenges faced by a female botanist and ecologist born in Melbourne, conducting scientific research atop the Victorian Alps in the 1940s. A time of poor transport, communication and with the discipline of ecology in its very infancy.

ABOVE: Maisie at Blairs hut, with Frank Fawcett

Maisie Fawcett, also known as Maisie Carr and Stella G. Carr (after marrying her husband Dennis), made a significant impact to botanical science, not least through her contributions that have influenced several generations of scientists. Since childhood, inspired by her grandmother, she developed a deep passion for plants. In 1932, she embarked on her botany studies at the University of Melbourne. She excelled as a student, completing her Bachelor’s Degree in 1935 and her Master’s Degree with first-class honours in 1936. She clearly was an intelligent women with a desire for knowledge.

During the early to mid-twentieth century, the adverse effects of cattle grazing on the ecology of Victoria’s High Country ecosystems were relatively unknown. In 1941, in collaboration with the School of Botany at the University of Melbourne and the Soil Conservation Board (SCB), an investigation was initiated to study soil erosion and, more broadly, the region’s ecology. At that time, some areas of the High Country were remote and accessible only by horse, with limited communication. Given these circumstances, it was initially preferred to hire a male ecologist for the position.

However, Professor John Turner, Head of the School of Botany, recognised Maisie’s talent and invited her to undertake an ecological survey. As a 29-year-old post-graduate student, she was tasked with investigating the effects of cattle grazing, fire and rabbits depredations on soil erosion, which posed a potential threat to the Hume Catchment. At that time, it was recognised that the region was experiencing issues related to soil erosion and sediment deposition in water reserves. “It was known that the great fire after 1939 had given rise to considerable losses of soil from the catchment and it was my job to assess the seriousness of the situation”, wrote Maisie in a note published in “A Book for Maisie”, organised by her husband, Dennis J. Carr.

Maisie’s invitation was not by chance. She had previously been awarded scholarships to Melbourne High School and Melbourne University, demonstrating that others had already recognised and believed in her scientific abilities. She got several scholarships along her student life. Offering her this position was not a risky endeavour.

ABOVE: cattlemens hut, Bogong High Plains

Another reason she was offered the opportunity was due to the ongoing Second World War. Men were unavailable for such work. They were either off to the War or in reserved occupations. Maisie, then, fearlessly ventured into the remote and cold mountains of Victoria. The proposed salary was not enticing to most men, nor to Maisie herself, but she embraced the challenge. While her interests spanned a wide range, she was encouraged to focus her studies and not dedicate excessive time to exploring various subjects. In a letter to Maisie at the start of her work in the Alps in 1941, Turner wrote, “I hope that by steering you towards ecology, I have made the right decision – but I truly believe I have”. He was so right.

Moving to Omeo, a small, isolated town in Gippsland, she began her work, traveling long distances mostly by foot and horseback across the Hume Catchment area. Maisie had to learn how to ride a horse and confront challenging weather conditions, bodily fatigue, and arduous terrain. “I was supposed to make a survey of the whole catchment which was 5,347 miles – on my own! I didn’t have a watch and I’d spend all my money on bedding and clothes for the job”, said Maisie in an interview in 1988, according to D. J. Carr´s book on his wife. And, despite feeling very lonely at times and being dubbed with nicknames like the ” Miss Washaway,” “Woman from Pretty Valley,” and “The Erosion Girl,” Maisie formed friendships with some of the cattlemen in the High Country.

Through her research, she discovered that the stability of the Hume Catchment was at risk due to potential soil degradation in the Bogong High Plains, the high-altitude grasslands where grazier took their cattle over summer. In 1944, albeit temporary, she was appointed as the first research officer of the Soil Conservation Board.

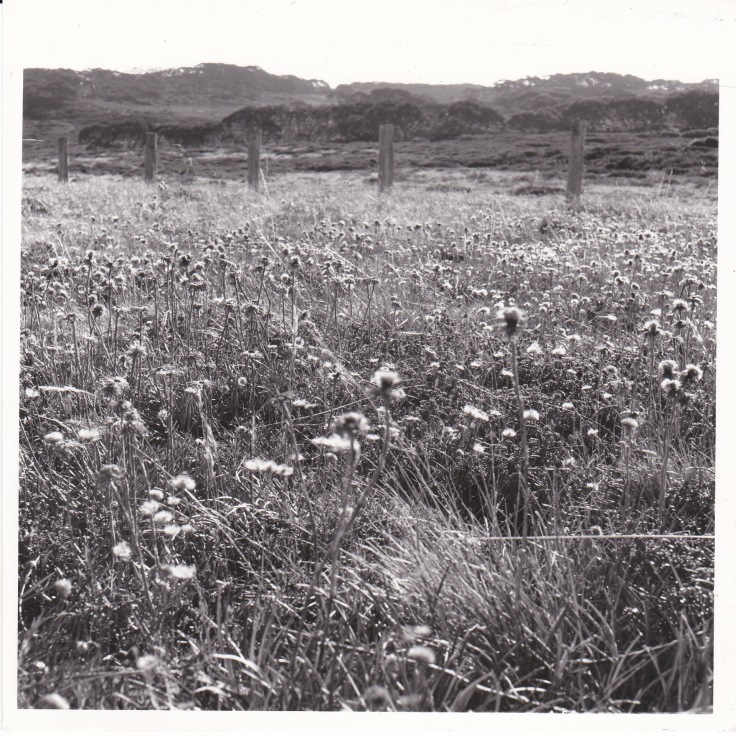

ABOVE: Maisie’s plot in Pretty Valley

In 1945, Maisie conceived ideas that would undoubtedly establish her as one of the most remarkable Australian scientists of all time. She proposed fencing exclosure sites in Rocky Valley and later, in 1947, in Pretty Valley. These areas, now known as ‘Maisie’s Plots,’ consist of two non-contiguous land areas located approximately 1 km apart.

The Rocky Valley exclosure, situated on alpine peatland, effectively restricted cattle and rabbit access (7.50ha), while the adjacent unfenced areas (5ha) allowed unrestricted grazing. In Pretty Valley, the exclosure excluded cattle (0.102ha), while an adjacent control area (0.102ha) permitted grazing. Both sites were equipped with permanently marked transects to monitor changes.

Over time, Maisie recorded vegetation changes, stream flow, and siltation rates within the exclosures. Her dedicated team helped monitor the plots using metal pins inserted into the ground to count and record plants that touched the pins. This method, now known as the ‘point quadrats method,’ proved to be a simple, accurate, and rigorous approach. Students with a keen interest in botany also joined Maisie Fawcett on the Bogong High Plains to assist with her work. The plots were monitored each summer for a decade. At the invitation of Turner, she went back to the region in 1964 to re-assess the progress of her research.

Through her work, Maisie provided scientific evidence that summer cattle grazing had detrimental effects on the condition of native vegetation and this contributed to soil erosion in the highlands of Victoria. She became the sole woman on the Bogong High Plains Advisory Committee, which from 1946 determined the number of cattle and their duration of stay during each summer´s grazing season. This was a remarkable achievement.

Her work has influenced land use and management. Grazing controls were implemented in the 1940s. Additional restrictions on grazing were enforced in the 1980s and 1990s with the establishment of the Bogong National Park. Her efforts, supplemented by new generations of ecologists, ultimately led to the complete cessation of licensed grazing in the Victorian Alpine National Park in 2005. As a result, not only did vegetation start to regenerate in ways that Maisie predicted from her careful observations, but the headwaters in the Rocky Valley plots also regenerated the species that are some important to their function.

However, we must not perceive this journey as an effortless or straightforward one. In fact, it was heroic, as Maisie had to navigate not only scientific, social, and weather-related challenges but also emotional hurdles. This becomes evident in the letters she wrote to Professor John Turner, which were subsequently published in her husband’s book.

She shared things like: “I spent all day on that plot, finally being reduced to rage and despair”; “I felt miserable and alone up there, with no help from anyone”; “I have been chiefly disturbed over selecting quadrats which will give an adequate amount of data”; “Today I was in desperate mood over footwear. I have worn out a pair of shoes”. Of course, Maisie had good moments, too. As she shared about Omeo: “It has turned green almost overnight and looks superb”; “a very grandfatherly child of five years comes in to see me every afternoon when I get home”. It was clearly worth her embarking on such a journey.

The Research Centre for Applied Alpine Ecology continues to monitor vegetation within Maisie’s plots every ten years. These plots represent some of the longest continuous series of ecological data-sites in Australia. Maisie’s work has been carried on by scientists across generations, enabling them to understand long-term trends in alpine vegetation dynamics in response to grazing effects, fire impacts, and climate change.

ABOVE: Maisie with unknown botanists

Within the scientific community, Maisie’s Plots are considered foundational to Australian ecology and hold significant historical value in Victoria. Recognising their cultural significance, Maisie’s plots were added to the Victorian Heritage Register on August 25, 2022.

Maisie Fawcett made history with her achievements, overcoming the obstacles she faced as a woman in a male-dominated field. Despite encountering discrimination and societal barriers, she demonstrated exceptional intellect, passion, and dedication to her scientific pursuits.

“Most women cannot understand how I can bear the life – the mud, the rain, the sun and the hardness of the life. However, I love it and the job I am doing is so intriguing. It could not be done any other way”, she shared on an interview to the Melbourne Argus in 1944. Her work opened doors for other women in the scientific community and continues to inspire future generations of female scientists.

Unbeknownst to her at the time, Maisie became an example of how far a woman can advance in her career and alter the course of history when supported and encouraged to follow her instincts, intuition, courage, and intelligence.

Maisie Fawcett’s story serves as an inspiration, highlighting the achievements of women in science and reminding us of the profound influence one individual can have in preserving our natural heritage for generations to come.

About the author

Karina Miotto is an environmental educator, journalist, TEDx organizer, and TEDx speaker. She resided in the Amazon Rainforest in Brazil for several years and collaborated with prominent NGOs. Holding a Master’s Degree in Holistic Science from Schumacher College, England, Karina has been in Australia since 2019. She has been actively engaged in writing, conducting workshops, and delivering talks, thereby disseminating her expertise and insights among community groups, events, festivals, schools, and universities. Additionally, Karina holds a casual employment position at Latrobe University.

You can contact Karina via Linked In: www.linkedin.com/in/karina-miotto

All images courtesy of Marion Manifold – personal archive.

HEADER IMAGE: Maisie and her horse Sheila.

January 30, 2024 at 7:11 pm

Maisie with unknown botanists; I think the one on the right is David Ashton, as a very young man.