Mountain Journal has slowly been compiling a collection of stories of ‘mountain icons’. In this contribution, Anna Langford reflects on her long connection to the Buffalo plateau.

How instinctively we reach for the superlatives – the oldest, fastest, biggest – when we want to distinguish something above its peers.

Mount Buffalo has no such claims on its fellow mountains: it is not the tallest, steepest, or remotest… and say nothing of its dismal snowpack that frays year by year.

There is only one superlative I insist on assigning it. To me, Buffalo has always been the grandest of our peaks.

All of us who have a deep love of a special place know that odd feeling of trying to explain why it is special, and being snagged by the realisation that our love is not simply a replicable product, attributable to its physical features. Buffalo’s vast grandeur has imprinted on me through a mélange of layered memories and sensations of the place. To borrow a phrase from Robert Macfarlane, it is my Mountain of the Mind.

But surely its majesty resonates with you, reader, and others?

For me, Buffalo’s thrill starts after 200 kilometres of chasing the white highway stripes down the Hume. I’m finally far away from Narrm/Melbourne, my tongue hanging out to begin the ascent up from the lowlands. On a clear day, cresting that hill just before Glenrowan, my eyes swing from their fastened focus on the blurring asphalt up to the right as Buffalo’s grand outline comes into view.

That magnificent banquet table in the sky, replete with chunky granite candlesticks and garlands of Buffalo wattle, ready for spirits to pull up chairs around it and merrily discuss celestial affairs. Indeed, for local First Nations people, it was a banquet table in a real sense: they gathered on the mountain each year to feast on Bogong moths.

Its girth is so wide, it looks as though a giant has taken a deep breath and puffed out his belly.

Buffalo is the proud gatekeeper to the rest of the alps, dwarfing the flatlands and beckoning me in. It has its own little sign pointing in its direction off the highway, so that when clouds thickly cloak its vista, I am still reminded of its welcoming presence. Every time, even when I am only passing it by to venture up another mountain, I feel like a tiny magnet quivering in the pull of its orbit.

At the foot of the mountain, I begin the coiling ascent up that road that feels too svelte for two cars to comfortably pass each other. It was built in 1908, long before all those monstrous SUVs were even a dream. Turn after turn lifts me up Buffalo’s giant flanks and into higher bands of cooler alpine air.

Towards the top, those immense slabs of granite heave into view, stunning my human sense of time into humble reverence. Our fastidiously counted minutes and hours blur into trivial tick-tocks that hold nothing to these custodians of geologic deep time.

Finally, I rise onto the plateau and enter its majestic world of tors, saddles and craggy edges, all like the turrets of a vast ruin. I like that Buffalo is a rambling plateau and not pinched to a central peak. It is unconquerable. Even when you stand at the Horn’s pointy spire, it is impossible to feel you have somehow summitted Buffalo, when the expanse of its terrain spreads out like a sea beneath. Put your flag away.

Yes, Buffalo is the grandest, welcoming you not on top of, but into, its stately grounds, where rocks the size of whales sit among snow gums with trunks so fat, you cannot meet your fingertips when you embrace them. How many of those ancients are now left?

These are the things I notice now. But they add brushstrokes to an old, old mind canvas that gives Mount Buffalo its one superlative claim on me: it is the place of my earliest memory.

In our endlessly photographed lives, do we truly recall moments from our childhoods, or are our memories merely regenerated scenes from revisited photos? In this case, I know for sure…

The trip my parents took me on to Mount Buffalo in the Millennium winter of 2000 is an anomaly in their meticulous records befitting a first child. We have no photos of that journey. They must have forgotten to bring that antique travel item – a camera.

At some point when we are young wide-eyed saplings, the things we see begin to burn themselves onto the roll of film in the brain that becomes our memory. That trip to Mount Buffalo is when the first slides on my memory spool flicker into view.

Two years old, I was clad in a puffy snowsuit by my parents who were determined to introduce me to the mountain and snow. We were staying at another travel antique: Mount Buffalo Chalet, built in 1910 by the Victorian Railways.

The images in my mind from that trip are like flash-lit photos: bright, indelible, fuzzy at the edges. In one, I am sitting beneath the creaking chairlift, Dad pouring a carton of apple juice on the snow and scooping up a handful for me to suck the sweetness through the ice crystals like a Sunnyboy. In another, I am stumbling in soft powder, baffled by the ground’s sudden porosity. Perhaps I formed my sense of balance against the worn slopes of that mountain, and have been dizzy on flat land ever since.

I remember my awe at the whole world turning white in its wintry attire. And I recall the grand rooms of the old chalet, where I felt small as a doll in the wide laps of fading armchairs and ate rice bubbles for breakfast in the beautiful dining hall.

The year was 2000: the start of a new millennium and the beginning of the end of an era for Mt Buffalo. In the years that followed, the Chalet doors were locked, the Cresta Valley lodge was lost to a bushfire, the chairlift squeaked to a standstill, and winters bring evermore fickle and fleeting snow.

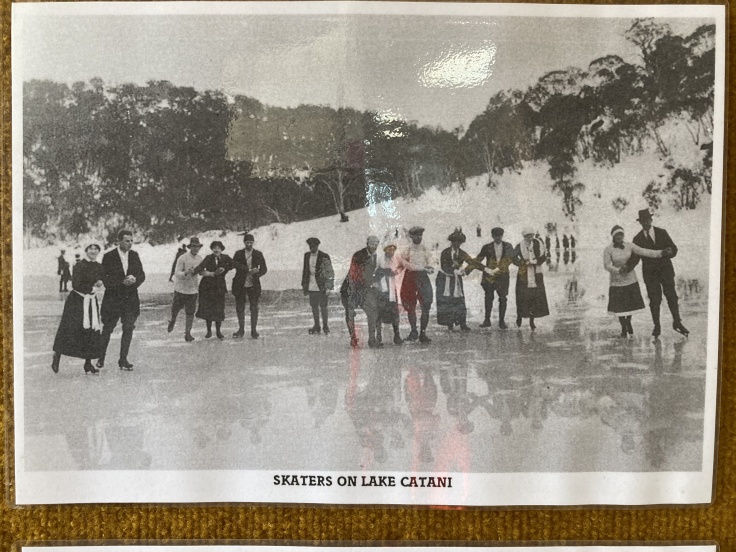

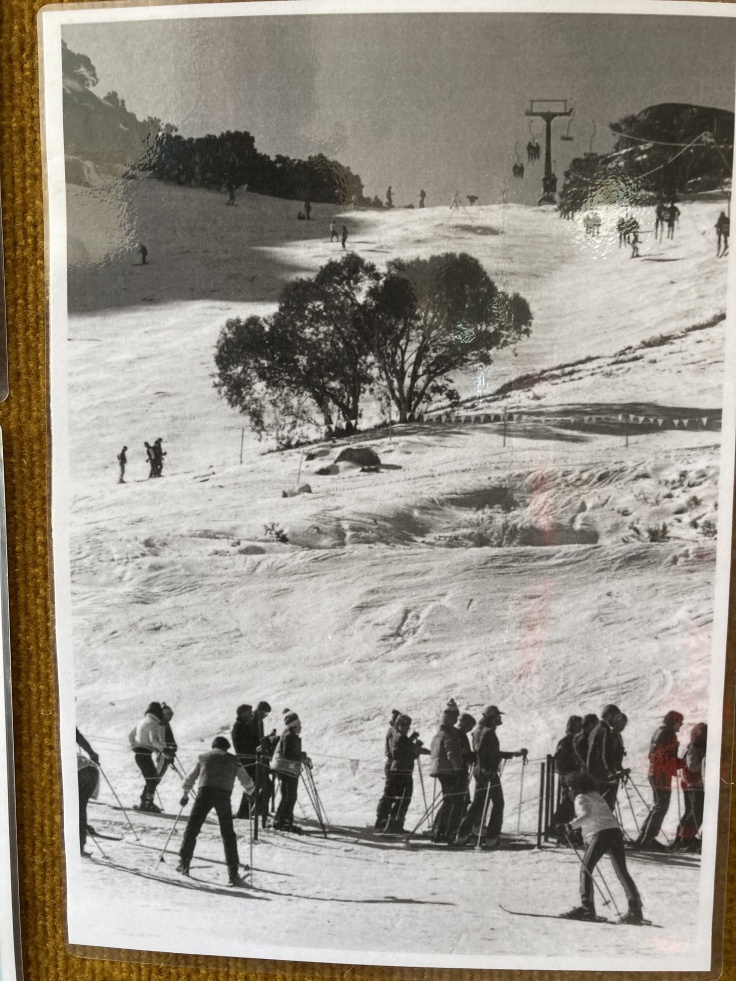

In many ways, the mountain is now a museum of itself. The collapsed rusting chairlifts give an abandoned theme park vibe; the Chalet resembles a grown up child’s old dollhouse that you can peep through the windows of to see the furniture still arranged just so. Dingo Dell kiosk has a pin-up photo display of Buffalo’s winter glory days of yore: skiers giddy with delight on fields of thick snow, ice-skaters interlinking arms on the gleaming surface of Lake Catani – ladies in skirts, men in caps.

The last time I visited was mid August of 2023; the time of season that should have been the height of winter splendor. As I gazed in disbelief at the photo of the ice-skaters, outside a ‘closed’ sign was nailed into the bare yellow grass on the toboggan slope. Our skis stayed dry in the boot of the car. Our boots got wet with slushy mud. We walked on Lake Catani the only way that was still possible – down the jetty, over the rippling water.

That year, at higher elevation, ski resorts including Thredbo and Hotham switched the chairlifts off weeks too early as the snow pack could not hold through the warmth. Resort social media pages took the line that ‘Mother Nature kept us on our toes’ and people said things like ‘Ah yeah, some years it just comes and goes’ with a light shrug of the shoulders. At Mount Buffalo, you can’t pretend that good winters come and go anymore. They are gone.

The Parks Victoria marketing department won’t be hiring me if I keep talking the place up like this. Oh, well. The truth is that it could never snow again at Mount Buffalo and I would still keep being pulled back to its magnificent form for the rest of my life, and would still populate it with those fuzzy two year old’s recollections of it as a winter wonderland. It will always be the grandest of them all and I cannot untangle the way it has grown into my heart and bones. As the poet Gary Snyder said, ‘That’s the way to see the world: in our own bodies’.

But to have known what Buffalo was, even through the thinnest thread of a single memory, is to carry a lifelong ache for the loss of a loved one. An early casualty of the climate crisis, Mount Buffalo should set off alarm bells for all of us who love winter and be our kick up the bum into the action needed to save our higher mountains from the same fate.

Let us still rejoice forever in the marvellous craggy cathedral of Mount Buffalo. Let’s start by protecting what is still precious about it (like those unburnt snow gums) and let it drive us to action through our reverence and love.

After ten years at Friends of the Earth, Anna is taking some time to step back, recharge and have a think from a distance about where to put her energy next.

You can follow her on Instagram here > https://www.instagram.com/langford_annasophia/

There is lots we can do to protect the remaining snow gum woodlands.

You can read the rescue plan for snow gums here > https://www.melbournefoe.org.au/a_rescue_plan_for_the_snow_gums

The Victorian government should investigate the ecological health of these forests – please sign the letter here > https://www.melbournefoe.org.au/snow_gum_petition

Have a read of this pledge for a volunteer remote area firefighting team, who would be tasked with protecting areas like Buffalo > https://www.melbournefoe.org.au/vic_raft_pledge

April 21, 2024 at 3:36 pm

What a wonderful essay! I haven’t been to Mount Buffalo for many years. Indeed it’s hard to quantify it, except for its unquestionable beauty from a pallet of granite and snow gums!