As I walk up the trails at Mt Stirling towards the summit, I always enjoy this sign. As more and more people get into the high country on foot or ski or bike, its good to remind them that it is another place to the lowlands and forested country, and things can get nasty very quickly. I also reflect that, with numbered sign posts and maps on pretty much every intersection on the mountain, it is almost impossible to get lost (yes, I know, people still manage to do it).

And I love the ‘map and compass’ note. It feels almost quaint and old worldly. And it makes me think about how our ways of navigating have changed so profoundly in the space of a few decades.

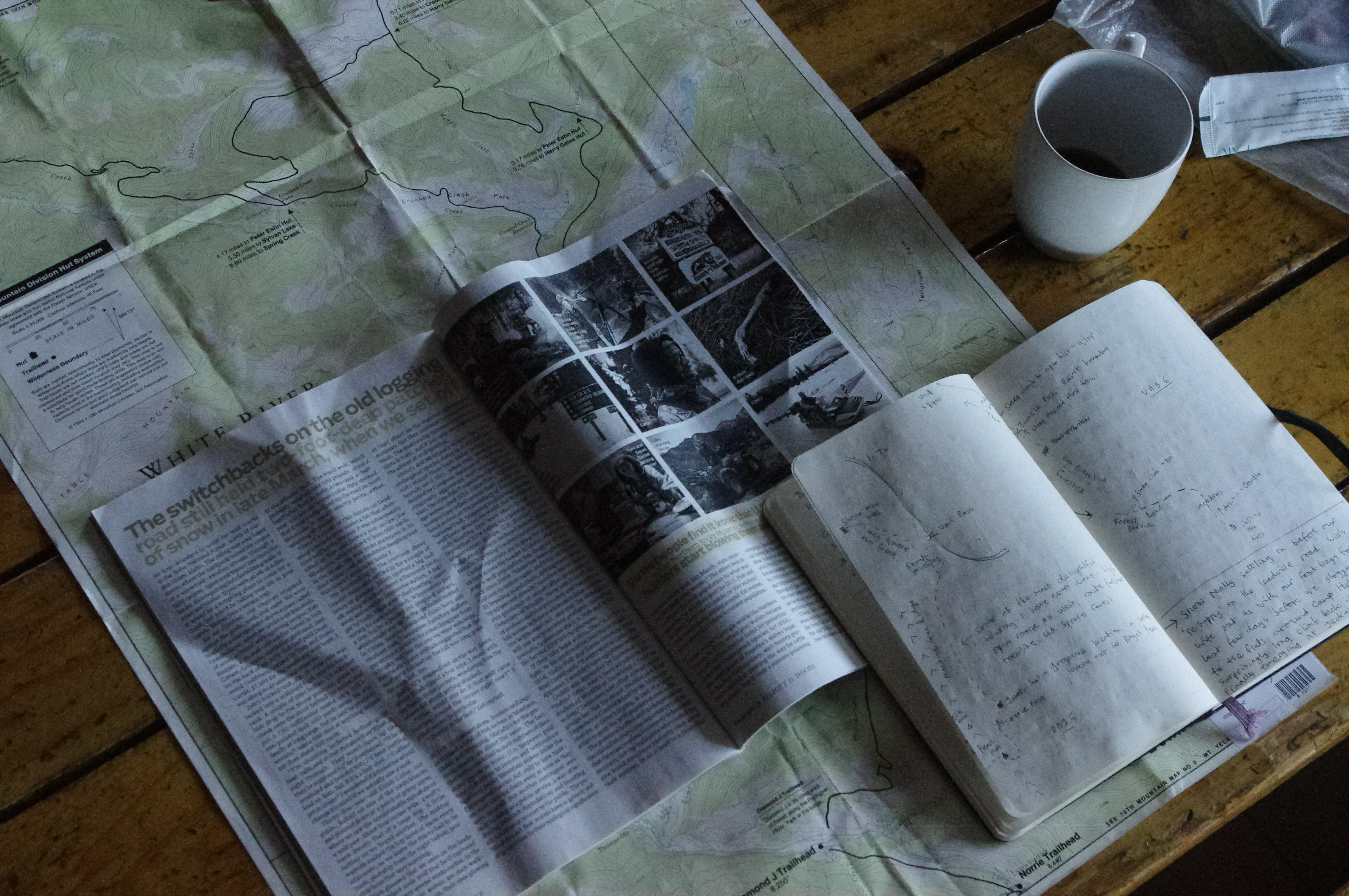

While I love all the technological innovations that have made outdoors gear lighter and better, I remain stubbornly old school when it comes to use of map and compass in the mountains.

I admit that from time to time when I have found myself to be a bit ‘geographically embarrassed’ that I have resorted to a quick look at the Footpath app – the free version has pretty basic layers of info but can be relied on to show where you are relative to that track you strayed off.

I understand the value of online maps and the many map related apps. I also get that there is a transition to online versions of traditional maps (for instance, I mourn the loss of the paper copies of the amazing 1:25,000 maps of Tasmania, which always seemed more like beautiful practical art than just a way to find your way around central TAS).

I also think that its wise for people who spend a lot of time out in the wilds to learn how to use a map and compass. You know, for those times when the batteries fail, or the phone gets dropped.

But without getting all on the soapbox, I also think that it enhances the experience of being in the mountains. A map requires you to be aware of the terrain, weather, animal pads and vegetation in a way that using a GPS does not. I do think there has been a general dumbing down of awareness of landscape and nature in society in general, which comes from a multitude of sources and a range of reasons. Learning how to use a map doesn’t change that, but it can tune you in to the land you’re passing through in a way you will never experience if you’re reliant on a screen.

My friend Kelly Van Den Berg, who recently established Gippsland Adventure Tours with her partner Paddy told me that the navigation courses they offer are hugely popular – with many people wanting to learn navigation as an adult (rather than when initially wanting to get into the backcountry). Good to see the transition to reliance on online maps and apps isn’t just a one way street.

Gippsland Adventure Tours. Find out more here. https://gippslandadventuretours.com/

You can find details on the navigation courses they are offering through Alpine Access Australia here. https://www.alpineaccess.com.au/alpine-navigation/

What apps are you using to navigate in the backcountry?

I like these ones – what are you using, and what’s good about them?

Footpath. Just a basic contour, road and track app. But it does the job.

Fat Map.

All Trails.

Alpine Quest.

Gaia GPS.

FarOut. ‘FarOut is the number 1 app for thru hiking, long distance hiking, biking, and paddling.’

OpenStreetMap (OSMAnd – OSM Android).

Maps.me. Allows you to download maps for use on your phone/ device while you’re offline.

Windy. Always a great addition to a map and compass – wind direction and the other layers are excellent for making decisions about travel and camping spots.

Leave a comment